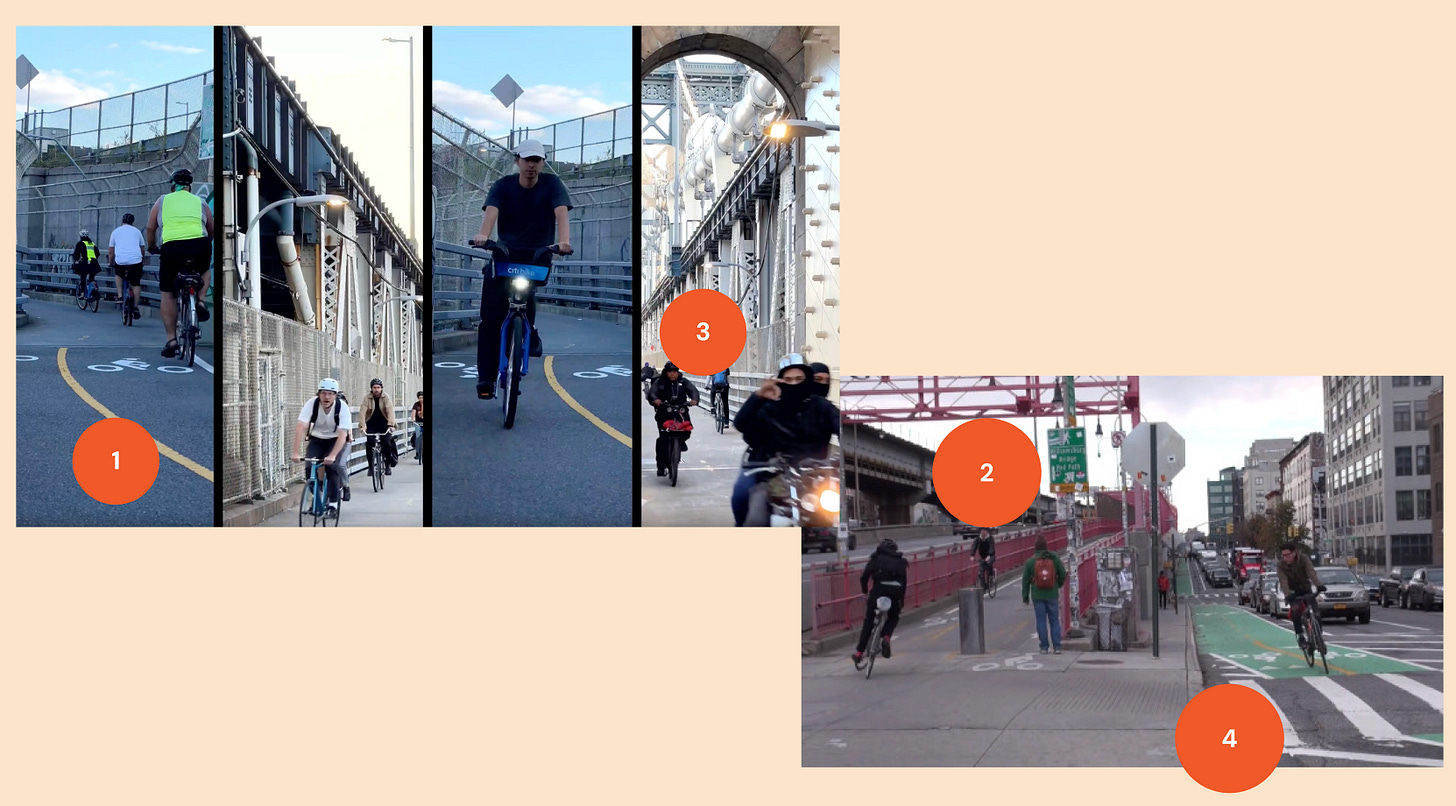

Biking over the Three Manhattan Bridges

A case study on how three iconic bridges finally added bike lanes

While I’ve been looking into micromobility, I dived down a small rabbit hole about the bike lanes on the three bridges downtown. Hovering as iconic fixtures connecting the boroughs, their biking lanes have come to be important paths I take to get home. So I decided to put together what I learned about its history and how they came to be.

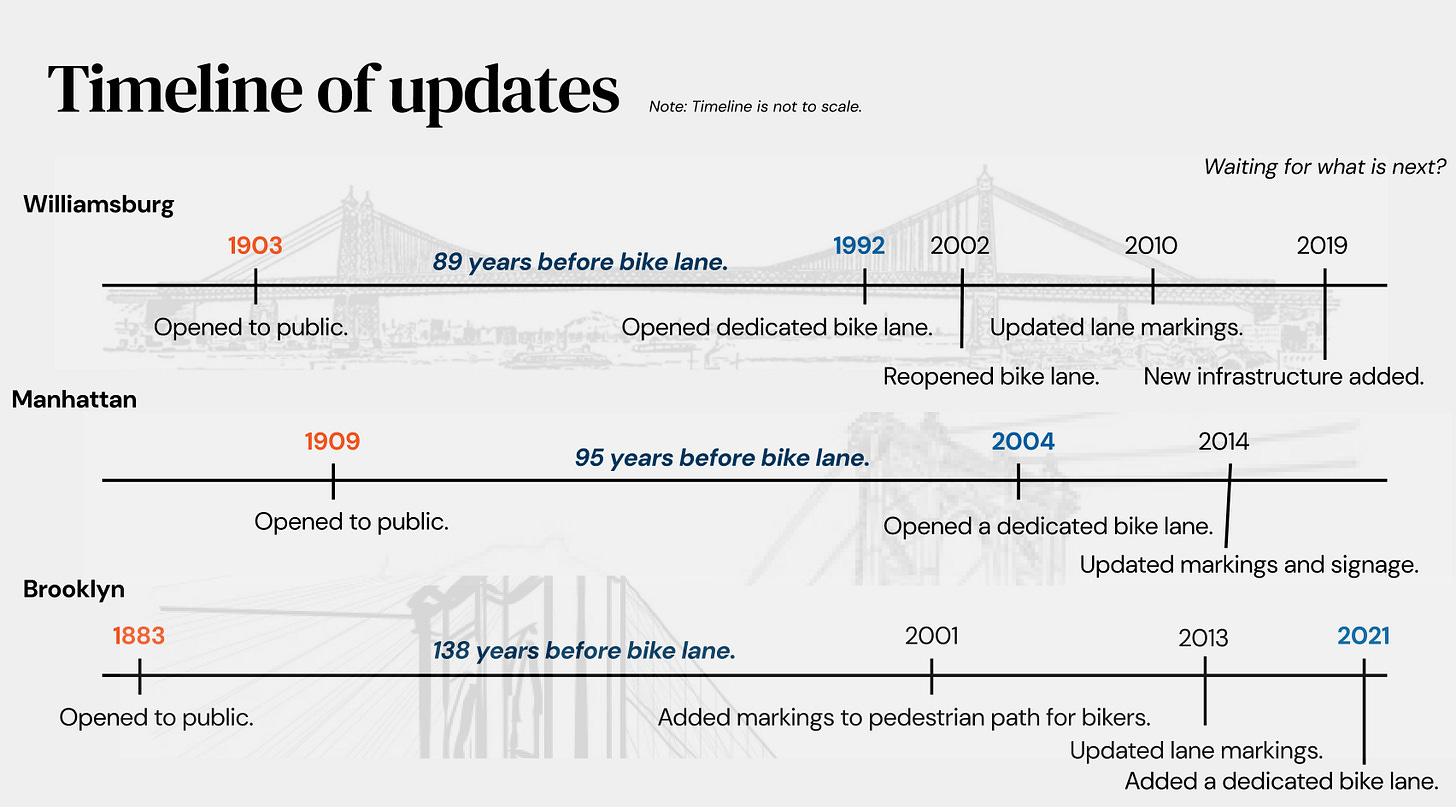

All three of the bridges have been critical in shifting lower Manhattan into a vibrant hub, growing residential and industrial centers on both sides across the river. Created in the late 1800s, early 1900s, the bridges were built with pedestrians, horse-drawn vehicles, and streetcars, before the addition of the subway.⁴ cyclists could originally bike where they could on bridges, when they first opened.

Post WWII, car traffic increases and streetcars are discontinued, increasing more car use. Some pedestrian walkways are kept, such as on Brooklyn Bridge, but Williamsburg and Manhattan had to update and restore accessible walkways over the past decades.⁴

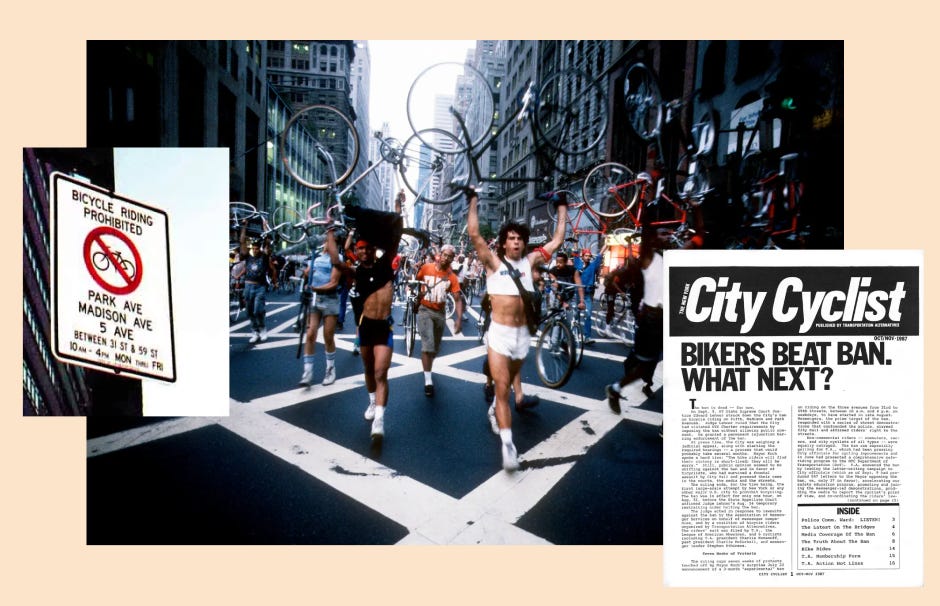

The city, fearing safety concerns with cars, quickly banned biking on the bridge roads, leaving bikers to pedestrian walkways. Yet, campaigns for dedicated bike lanes did not find much success due to the perceived notion that bikes were more for recreational use, rather than as a mode of transportation.⁴

Cars became the dominant mode of transportation, decreasing support for bikes.

Throughout the 1900s, there continued to be a lack of dedicated bike infrastructure on the three bridges as bikers in the city faced major lash back and disgust.⁵

Bikers are also often not one coalition⁶, leading to conflicting ideas and incongruent messages⁷.

Still, bikers kept to the available pedestrian walkways as the main way to cross the between the boroughs. Over time, regulations got added to specify where biking could and could not exist.

1900s-1920s: No explicit rules barred cyclists completely, but peak hours and general vehicle flow first promoted automobiles, restricting bikes. Certain lanes were banned and sometimes bikers had to dismount and walk with pedestrians. Sometimes walkways were also closed during busy hours.⁴

1930s-50s: NYC Traffic Code established regulations for vehicles, including bikes, requiring them to follow the same rules as motor vehicles. Enforcement often strictly banned bikes during rush hours.⁴

1960s: NYC Traffic Regulations were passed to force cyclists to use the pedestrian walkways when crossing bridges across Manhattan.⁴

1970s-90s: Organizations like Transportation Alternatives and an increase in riders due to transit strikes, began pushing to add bike lanes, challenging the existing regulations.⁷

Early talks from the community and developers around how to add bike lanes focused on how to integrate biking with walking paths and repurposing car lanes.⁴ Questions revolved around the logistics, space, conservation and finances.

How could the city best connect the bikes to existing paths, and what would the path look like? Was there enough space available on the bridge pathways for bikers to move quickly and safely Could a bike path be created without adding or removing sections of the bridge?¹¹ Where is the funding coming from to create a safe and efficient bike path?

Over the past 30 years, the addition of bike lanes finally provided the separation groups have been asking for.

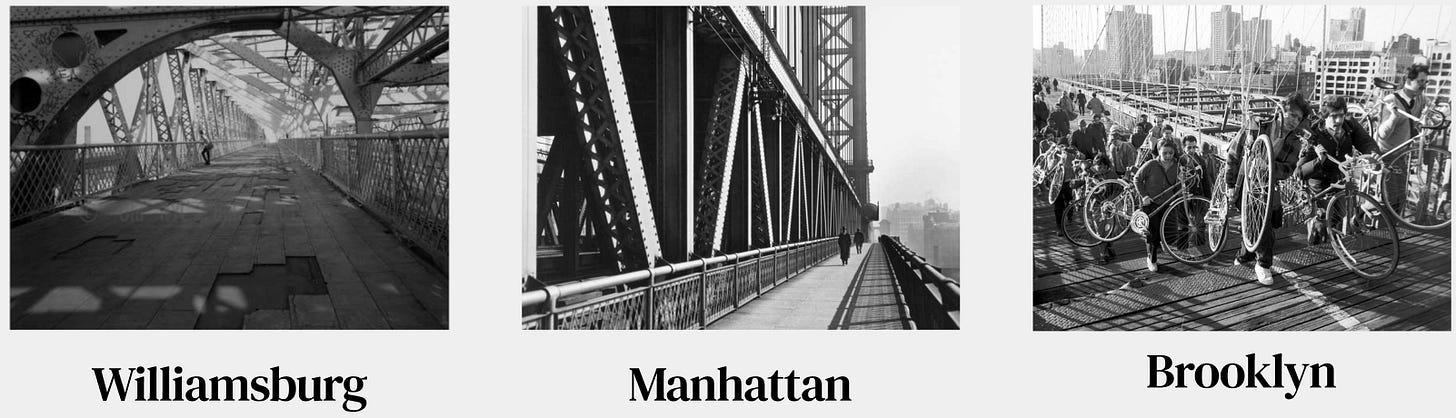

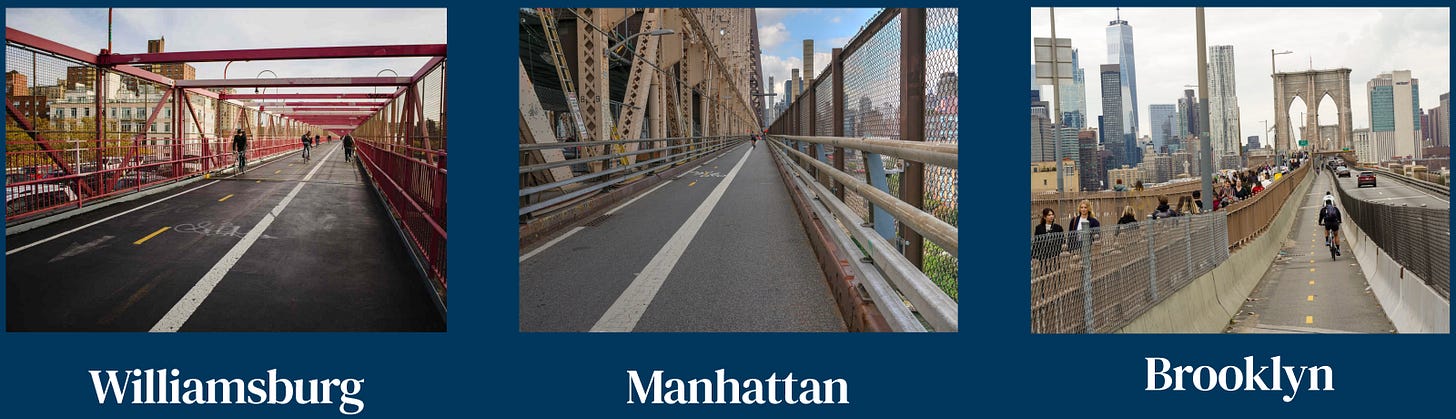

Williamsburg Bridge

No coordinated campaigns are seemingly made to call for a bike lane before the late 1980s⁸, where efforts with Bike NY and Five Boro Bike Tour led to garnered interest⁷.

Originally replacing a walking path in 1992¹ as part of the bridge renovation project, the north side bike lane was reopened in 2002¹² after reports of lead.¹³

Manhattan Bridge

Bikers were forced to walk their bikes, with groups like Kings Wheelers Cycling Club in 1940⁴ proposing to Robert Moses pay for a dedicated bike lane, but to no avail.

Bikes shared the pedestrian path in 2001, after being closed for 20 years², before receiving a dedicated lane in 2004 on the east side of the river, away from walkers.

Brooklyn Bridge

Coney Island Cycle Path proponents in the early 1900s⁴, or transit strikes in the 1980s, campaigned officials for a path, but was unsuccessful in swaying anyone.⁹

Pedestrians and bikes fought for space up until 2021³, when the city refurbished a car lane with a bike lane, moving bikers back to the lower level of the promenade.¹⁴

Much of the public reception was positive, with ridership across the bridges continues to prove the effectiveness of adding the bike lane. As of 2022, Brooklyn had 4000 riders a day¹, Manhattan with 6000 riders a day², and Williamsburg: 7000 riders a day³.

Separation of riders from pedestrians has also led to a general positive sentiment¹⁶, as bikers do not have to fight for space. “I didn’t have to scream at anyone in the way today” said a cyclist riding on the new Brooklyn Bridge bike lane¹⁵ Another cyclist riding across the Williamsburg Bridge said, “It’s a pleasure ... The best part is going across and seeing all the cars backed up.”¹⁷

But that doesn’t mean there isn’t feedback on how to make the bike lanes better. These issues are focused on:

Narrow steep paths, with tight corridors next to bikers coming in the opposite direction separated only by lines of paint, often with concrete barriers, left-behind construction materials, chained fences obstructing paths.¹⁸

Signs and markings on the bridges are also inconsistent, leading to confusing decisions on where to enter the bridge. .¹⁹Lack of lighting is also a concern at night. ²⁰

Electric and motorized vehicle speeds on the bridges remain incredible dangerous, given the lack of space. ²¹

Inconsistent connections with the existing bike lanes still remain, leading to congestion and bottlenecks at the ends of the bridges. ²²

I personally hold all of these gripes as well, having biked over all of these bridges before myself. I’m especially annoyed with the narrow space and sharing spots of the bike lane with pedestrians on the Williamsburg bridge.

Fixing the issues and problems with the existing bike lanes will take time and continued advocacy, as DOT and the Mayor slowly make changes. ²³

Debate around mopeds driving continue to be a major concern, exacerbated by the limited space on bridges²⁴, leading to questions around police enforcement. Transportation Alternatives continue to push for improvements across the board for bridges, including the #Bridges4People²⁵ campaign that advocates for bigger spaces. Developers are also challenging architects and innovators to reimagine what the space could look like through proposal contests²⁶.

Steps are moving in the correct direction, albeit incredibly slowly.

To dive deeper or read more, feel free to check out my resource page. You can also view a version of this in a presentation.

Also a fun little article to read about trying to take photos of the Williamsburg bridge is here in Streetsblog.