Making Room for Homes in NYC

New York City does not have sufficient housing for its residents and requires urgent action to address the shortage.

New York City is in the midst of a housing crisis.

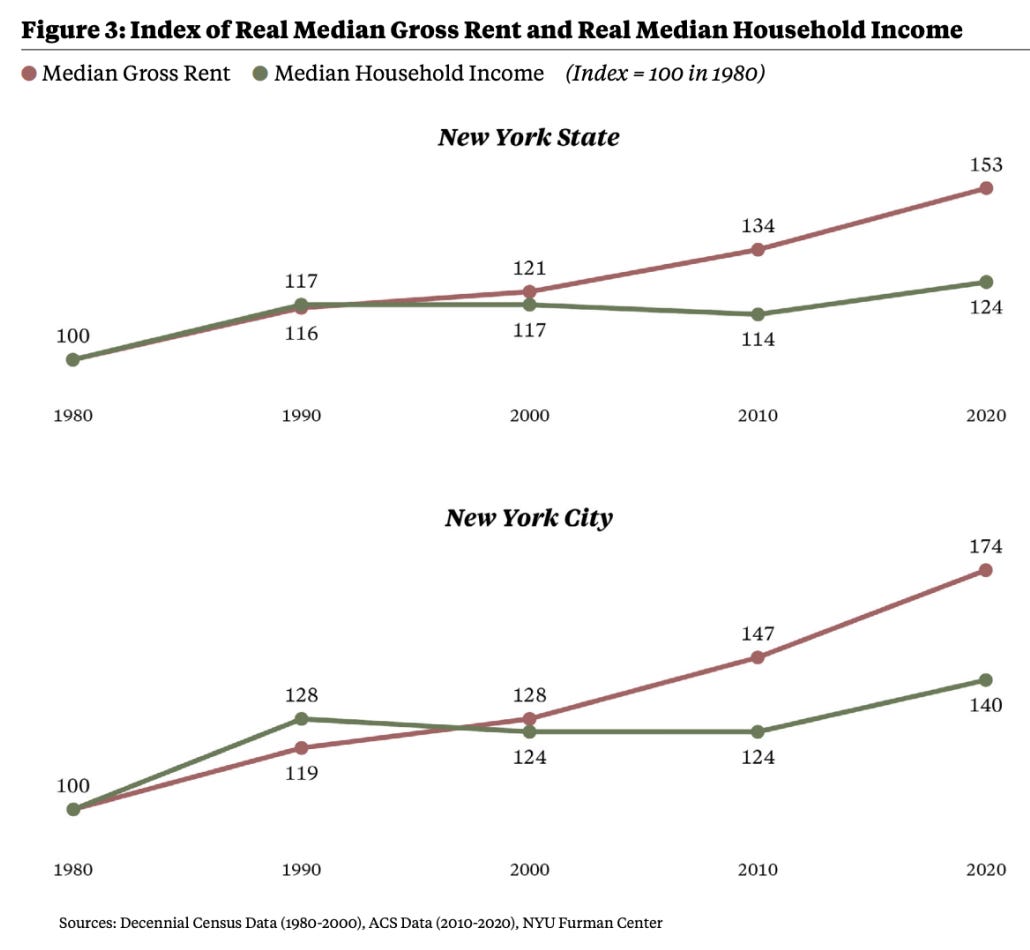

Housing costs are consuming an ever-larger portion of household budgets, with over half of the city’s households are rent-burdened. Median rent has outpaced median income over the past two decades. Vacancy rates have plummeted to an all-time low of 1.4%, leaving fewer apartments available for rent than ever before.

While rents briefly dropped during the early stages of the pandemic, they quickly rebounded, leaving many New Yorkers questioning if they would be able to afford to continue living in their communities.

New Yorkers from all walks of life face limited housing options. The young struggle to afford their first homes or pay rent. Seniors and older adults cannot downsize their large houses. Families are constrained by housing choices. These pressures exacerbate and reinforce inequality across income and racial lines. Employers also find it increasingly difficult to attract talent to a city without adequate affordable housing, stifling economic growth and productivity.

Outdated zoning regulations, lengthy development timelines, and inflated construction costs compound the problem. There is little debate that NYC needs to build more affordable housing, and quickly.

Here are three key approaches to achieve this goal:

Streamline the development process

Remove exclusionary zoning and encourage inclusionary zoning

Eliminate parking mandates

Policy Option #1: Streamline the development process

The development process in NYC is bogged down by antiquated barriers that inflate costs and delay timelines. These barriers ultimately result in higher rents, fewer affordable units, and lost job opportunities.

The key governmental processes that cause delays include:

City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR): Required by the State Environmental Quality Review Act, CEQR evaluates the environmental impact of any development of discretionary action, including those that need city funding, require permits or approval of a city agency, or those directly carried out by a city agency. This process adds over an estimated $4 billion annually to construction costs, with traffic studies alone taking six months to a year.

Land Use Approvals (e.g. ULURP): The Uniform Land Use Review (ULURP) is a lengthy process mandated by the City Charter, often taking up to at least 205 days to complete. Initially created to democratize the development process from bureaucrats like Robert Moses, it’s now estimated that this process can cause significant delays. For example, a delay of three months of a 100-unit project can add an additional $1.4 million in costs.

Department of Buildings’ Permitting Process: Leadership changes, communication issues, and a lack of a centralized approval tracking system further delays construction.

All three are important to protect the environment, require public participation, and ensure public safety; yet, they have all become unnecessarily complex, costly, and time consuming. To cut the red tape and remove administrative burdens, the NYC government must make critical decisions and technological advances to speed up the process.

Mayor Eric Adams’ “Get Stuff Built” roadmap outlines over 100 initiatives to address these issues. Here are a few proposed solutions:

CEQR: Exempt small housing developments (up to 200 units) and updated the outdated analysis method to reduce time spent.

ULURP: Shorten the pre-certification phases and allow for earlier community board reviews to decrease timelines by up to two years.

Department of Buildings Permitting: Establish a centralized citywide portal to consolidate all permitting processes and improve coordination and ownership.

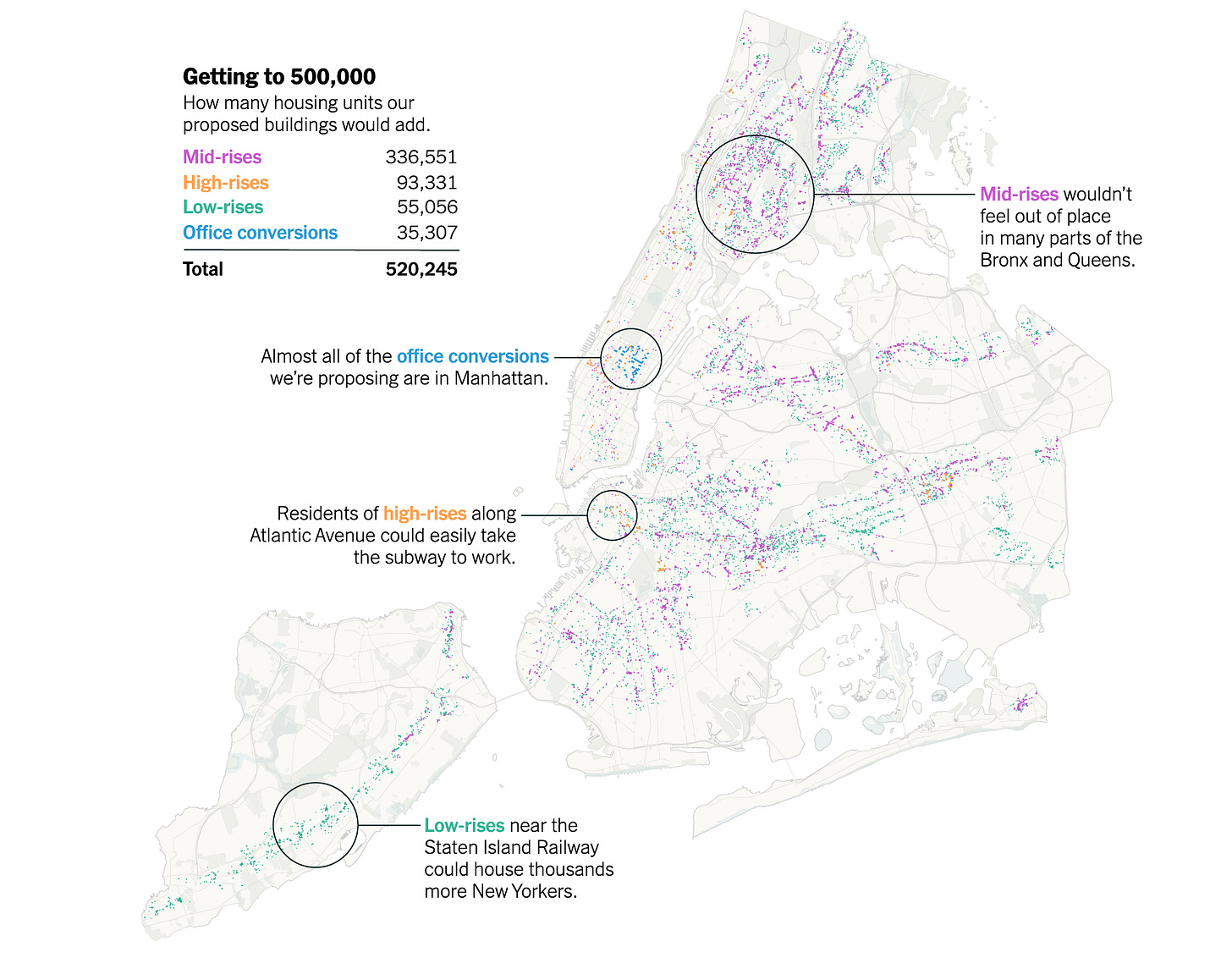

Policy Option #2: Removing exclusionary zoning

Exclusionary zoning restricts housing types in certain neighborhoods, often to preserve real estate values and exclude lower-income demographics. Low density districts cover 4% of the city’s land, while housing only 28% of the population, producing housing at half the citywide rate.

Opposition is often known as NIMBYism, or Not In My Backyard, and is most vocal within these areas of low-density and high homeownership, such as Staten Island and outer Queens. In 2023, Staten Island built less than 1,200 new housing units, and the outer edges of Queens built only 3,000 housing units.

The key zoning policy changes include:

Single-family zoning: Prohibits multi-family housing in many areas. Allowing for duplexes or triplexes on single-family lots could add an additional 419,000 homes.

Minimum lot sizes: Restricting housing size limits the opportunities for smaller, more affordable units in spaces previously deemed to be too small, as well as opening units to be built near transit hubs and town centers. Houston’s reduction in minimum lot sizes added 39,000 townhouses in 13 years.

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs): Often banned and restricted, ADUs can be added to existing single-family homes, hidden as apartments above garages or as small backyard units. When California mandated ADUs, Los Angeles County added 26,000 new homes in just three years.

Transit Oriented Development (TOD): Surprisingly controversial, TOD is focused on building homes near transit to help people move around the city easier. The challenge is often tied with zoning regulation, limiting the types of houses that can be built near transit.

Office-to-apartment conversions: With the gradual shift to work from home, many office buildings remain vacant as landlords and businesses continue to maintain these spaces for potential office buildings. Incentivizes or punishments should be enacted to convert these buildings to homes.

The biggest fear NIMBYs bring up about these policies is the physical change they will see in their neighborhood. But by definition, these three changes bring minimal aesthetic change in the local environment.

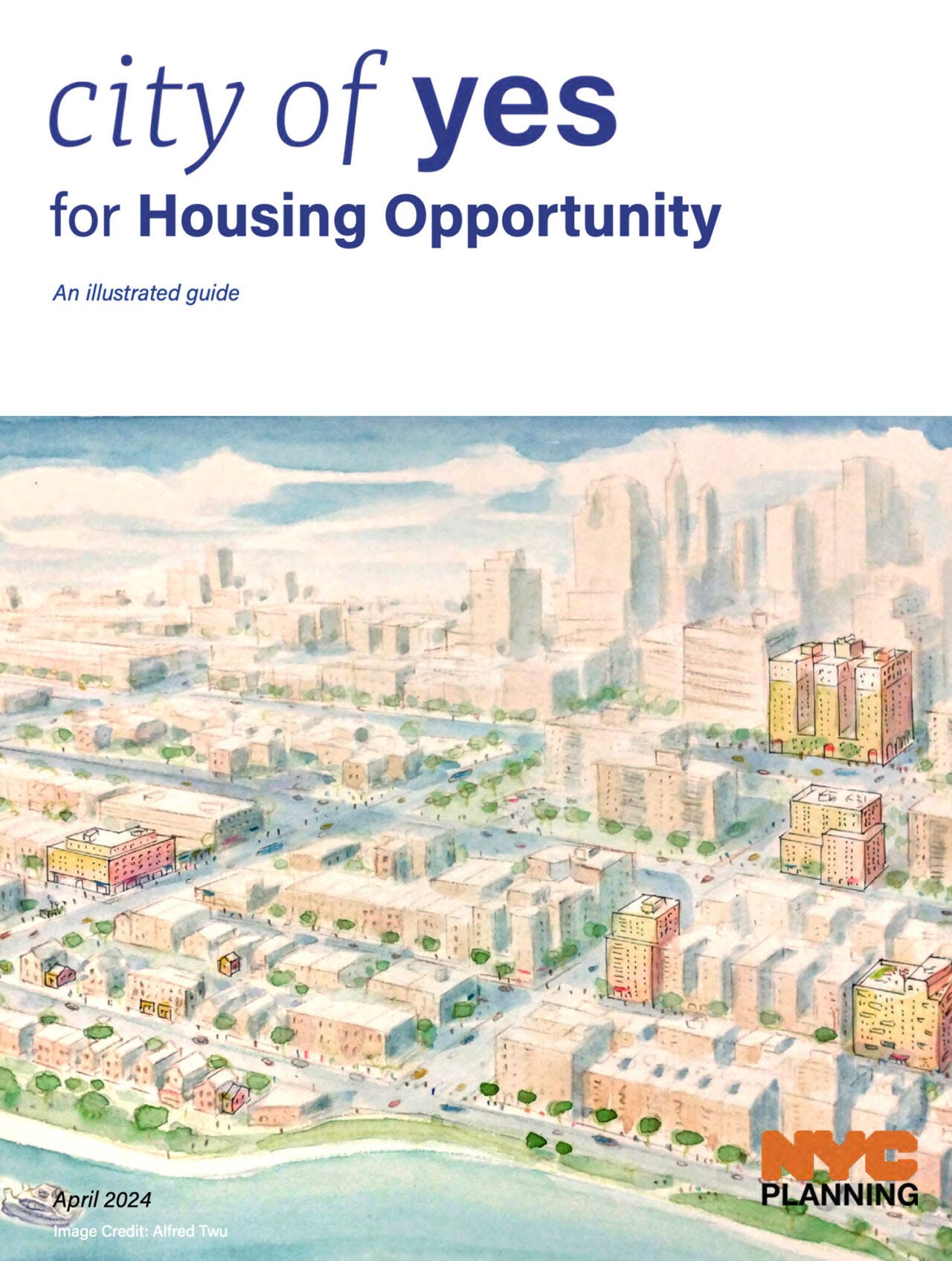

Governor Kathy Hochul’s proposal to build 800,000 new homes and Mayor Adams’ “City of Yes” initiative focused on these proposed solutions:

Single-family zoning: Allow for multi-family housing in low-density areas to build denser housing units together.

Minimum lot sizes: Reduce the minimum required lot size to take advantage of previously prohibited available space.

ADUs: Legalize and incentivize ADUs to encourage homeowners and developers to make use of underutilized private space.

TODs: Activate underutilized lots near rail transit (0.5 mile away) and overbuild on top of upzoned low rise buildings like single story retail and grocery stores.

Office-to-apartment conversions: Renovate existing office infrastructure for studio and 1-bedroom apartments, while also increasing common space in parts of the office building that can opened back up to the public.

Yet, both projects faced push back against these very policies by NIMBY groups in low-density districts. Overcoming opposition requires clear communication about the minimal physical impact and the significant housing gains these policies provide.

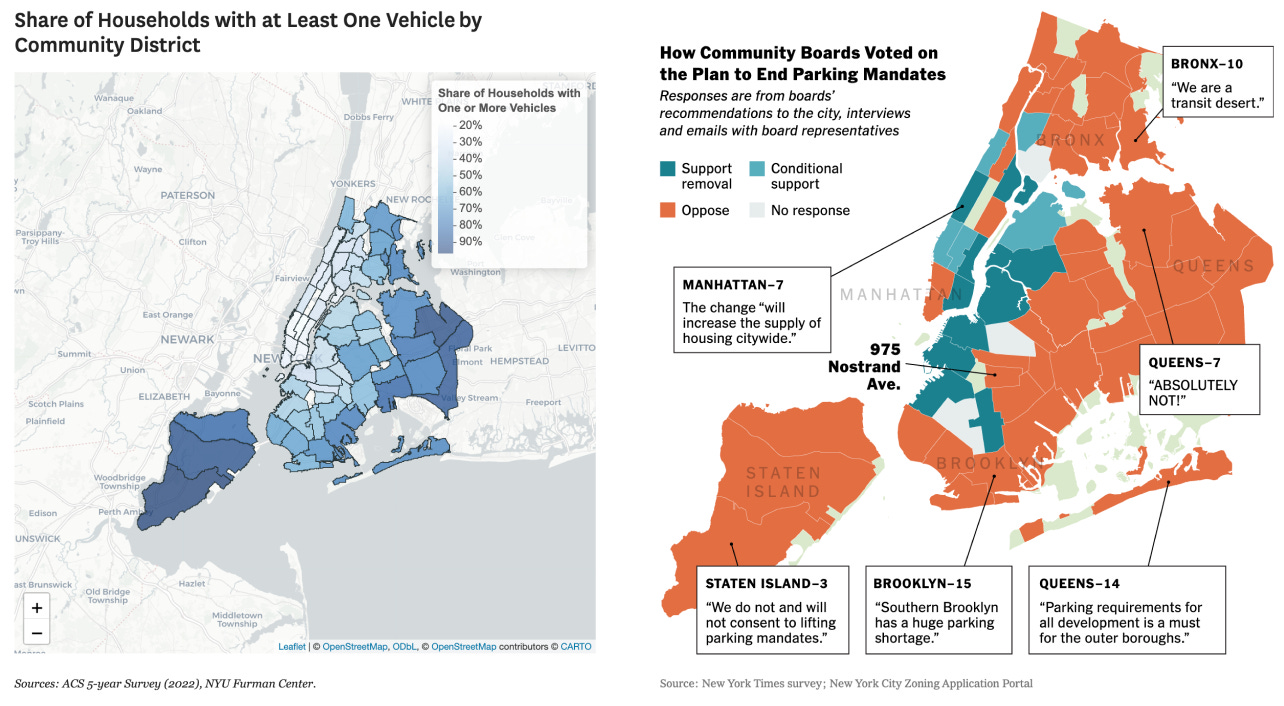

Policy Option #3: Eliminate parking mandates

Parking mandates, established in 1961, require developers to provide off-street parking for new housing units, consuming valuable space and inflating costs. In space-constrained NYC, these mandates hinder efficient land use.

Today, NYC is home to an estimated 5.4 million parking spaces, with 33% of this built for private and residential off-street parking. This totals to around 286 million square feet and an estimated $89 billion in development costs. Parking rules are also often complex, requiring developers to navigate an unnecessarily convoluted patchwork of regulations.

The proposed solution is simple – eliminate parking mandates.

This policy is straightforward to implement and yields immediate, visible benefits. It reduces costs, creates space for housing, and sets the stage for broader reforms like streamlining processes and removing exclusionary zoning.

Parking mandates block the construction of an estimated 30,000 units across NYC, making it easier to construct ADUs, TODs, and the other missing middle housing. It reduces the complexity in zoning codes and increases the speed in which housing can be built.

“We can never lose sight of the fact that many [of] those who pushed for the 1961 Zoning Code aimed to promote... segregation.”

- Eric Adams, September 2023

Numerous studies show that parking mandates are unnecessary, as market forces naturally adjust supply. Eliminating these mandates will free up space for additional housing and reduce development costs, making it a high-impact, low-resistance policy change.

Future residents will thus be able to pay decreased housing costs, while also receiving other benefits including improved street safety and future transit investment. Cities that have eliminated parking mandates, like San Francisco and London, have found that the market adequately responds to the amount of parking needed.

How to get started

Successfully implementing any of these policies will require collaboration across multiple stakeholder to ensure a smooth transition and address concerns effectively:

City Council Members: Sign onto legislative approval and foster local community support.

Community Boards: Engage residents to address their concerns about parking availability and potential neighborhood impact.

Urban Planning Experts: Provide data-driven insights on the benefits of removing parking mandates.

Real Estate Developers: Encourage buy-in by highlighting cost savings and increased housing potential.

Transportation Authorities: Continue building public transit options in transit deserts to mitigate potential parking demand.

Advocacy Groups: Mobilize support from organizations championing affordable housing and sustainable urban development.

The primary advocates will be council members and community boards located in high density districts, urban planning experts, real estate developers, transportation authority and other advocacy groups. But the biggest challenge will be NIMBYism council members and community leaders that live in low density districts.

As mentioned above, reduced costs, better space, and foundational support will receive love from all of our advocates. To build a little bit of housing in each neighborhood requires our opposition to agree and visually see the benefit, not just for new housing, but how eliminating parking mandates will also benefit them. We must help them reimagine what this space could be better used for and how their part in helping NYC add more housing benefits everyone, not just new residents.

Addressing NYC’s housing crisis requires bold, coordinated action. Advocates for more affordable housing must continue to push to build more housing, so the city can pave the way for a more affordable and inclusive future.

These three policy agendas are critical to achieving this goal and addressing the NYC housing crisis.

Streamline the development process

Remove exclusionary zoning and encourage inclusionary zoning

Eliminate parking mandates

The city can reduce development costs, maximize land use efficiency, and open the door to build affordable housing. This reform not only aligns with broader city planning goals, but sets a precedent towards equitable housing policies for cities across the globe.